Rather than redefining or rejecting the term “avant-garde,” we offer an alternative: en dehors garde (listen to pronunciation).

Taking a cue from classical ballet rather than warfare, we propose the term en dehors garde to describe the strategies of writers and artists whose mode of experimentation does not conform to the “martialised,” oppositional stance associated with the historical avant-garde.1

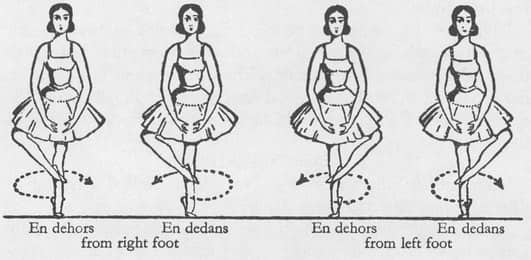

En dehors means “toward the outside” or “turning outward.” In ballet, it describes a directional movement: a dancer’s leg moves outward and away from the supporting leg, where the weight is centered. It is an outward movement, reaching outward and beyond the center.

En dehors is a classical ballet term meaning ‘outward.’ En dehors is added to other steps and terms to describe which way a step should be moving. For example, a pirouette en dehors would mean that the dancer would turn ‘outward’ away from the supporting leg.

The en dehors movement also has a circular quality: the dancer’s leg curves outward with an eye toward that center as a point of return. The circular motion does not follow a linear trajectory. It is also not hierarchical, having nothing to do with who is in front or behind.

A New Feminist Theory

Perhaps you can already see the metaphoric advantage of the term en dehors garde for a feminist theory of the avant-garde. “Avant” means “before,” implying that artists are in front of culture and ahead of their time, arranged in a spatial and temporal hierarchy, militant and prepared for attack. “En dehors” means “toward the outside,” implying that artists are turning away from the center or norm, moving in a circular motion, with an eye toward the center. Upon return, the center is transformed, adjusted, and reformed by the arc of the revolution.

Rather than assuming a militant position at the forefront of culture, women, people of color, and queer or disabled artists often came from the outside and circulated on the margins. They rarely enjoyed the power, privilege, or authority derived from membership in the institutions of art, or even in the countercultural, avant-garde circles that challenged those institutions. Instead, they worked and moved strategically to transform gendered, racialized literary traditions and visual cultures that excluded or objectified them.

Susan Rosenbaum’s theory of women’s poetic “experiment in an American context” might be extended to describe a transnational en dehors garde, in that the experiments do not “reside in a particular form” and are not contained by a particular avant-garde movement.2 Instead, en dehors garde experiments might be “more productively understood as a stance toward the work of writing [and art-making], and as a method of generating that writing [and art]” (Rosenbaum 326). Gender is a “key thread” in the complex fabric of such experimentation, involving both “challenges to the norms of gender and sexuality” and “important cross-gender alliances” (Rosenbaum 326). In addition, ambivalence often characterizes the stances and inflects the methods of the en dehors garde, as it does more specifically among American women poets:

Women poets’ ambivalence about avant-garde affiliations evinces a wariness not only about the sexism and/or racism of avant-garde movements, but also about social and aesthetic categorizations. […] An experimental stance is often coupled with an acute awareness of language’s potential collusion with entrenched systems of power, history, and thought: the merit of any critical category depends on who is using the category and for what purposes” (Rosenbaum 329).

Understanding the en dehors garde as a set of stances and methods adopted in response to dominant artistic and literary structures and conventions requires re-positioning the creative work in the biographical and historical contexts of the people who produced it, as Rosenbaum explains:

If we regard experiment as a stance toward the work of writing, and as a method of generating that writing, literary history, particularly the history of the avant-garde, must be opened up and investigated anew. This involves not only the continuing recovery of forgotten and overlooked poets, but study of the infrastructure of experiment as it was being made, in anthologies, little magazines, middlebrow magazines such as Vogue and Vanity Fair, small press publications, poetry reading series, collaborations, gallery and exhibition catalogs, writing workshops, unpublished drafts, and letters. Women were actively involved in all of these pursuits, as poets, but also as visual artists, editors, publishers, translators, gallery directors, curators, and teachers. Widening our gaze to include the contexts that supported women’s experiments opens up new histories of the twentieth-century’s social and artistic networks and institutions. (Rosenbaum 334)

Our project attempts to widen our gaze to include the contexts that supported Mina Loy’s experiments, in order to initiate new histories of twentieth-century en dehors garde networks, many of which exist outside or on the margins of artistic institutions. As we discuss in subsequent chapters of this Baedeker, Loy’s en dehors garde stances and methods include but are not limited to:

- a different relationship to the audience or public from the celebrated avant-garde stance of bellicose aggression, in part because Loy didn’t enjoy the same power, authority, and freedom as her white male contemporaries, and in part because Loy was interested in art’s amative and democratic potentials;

- a different relationship to high, popular, and commercial cultures: Loy borrowed whatever traditions assisted her in executing her witty critiques and investigations of systems of power and performance, and participated in commercial culture to make a living;

- an ambivalent stance of simultaneously participating in and critiquing artistic cultures, institutions, and conventions, one that acknowledges complicity and entanglement in the very discourses, processes, and systems she criticizes;

- related to this bifocal perspective of simultaneous critical distance and complicit entanglement is an effort to both expose and erode divisions between opposed entities such as the public and private, the bum and the saint, the universal and personal, the hotly intimate and cooly ironic.

Even as we enumerate Loy’s en dehors garde stances and methods, we want to emphasize that they are shifting, provisional, and sometimes erratic or contradictory, refusing to cohere or provide stable groundwork for a unified theory of the en dehors garde.

In proposing the term en dehors garde, we are not trying to overrule existing theories of avant-garde, nor do we expect that the term “en dehors garde” will take the place of “avant-garde” in popular or academic usage. Instead, we imagine that our emergent theory of the en dehors garde might occupy the same stage as reigning theories of the avant-garde, but alter the choreography and bring new dancers and moves into view. Like the feminist avant-garde Sophie Seita describes, the en dehors garde “critiques previous, traditionally male dominated avant-gardes by attending to what has been excluded and what must remain provisional:”3

In this view, the allegedly anti-identity, theory-driven, hierarchical, and manifesto-heavy avant-garde is […] only one among many other possible manifestations of ‘avant-gardeness,’ rather than the measure of all others (Seita 163-182).

As Stephen Ross observes, the en dehors garde “also suggests the unexpected, that which comes from ‘dehors’ [outside], what can be guarded, and re-garded.4

A New Feminist Method

In proposing a new feminist theory of the en dehors garde, we have also sought to generate theory in a new way. We wanted to activate theory-making through a new, collaborative method enabled by digital tools and platforms.

Typically, theory is written by a lone scholar and delivered in a coherent, linear argument. We have instead generated theory in an experimental, collaborative way:

- by collaborating with one another on the production of this online Scholarly Baedeker, and

- by using social media to orchestrate a digital flash mob. In Summer 2018, dozens of writers and artists turned out to contribute short position statements in the form of digital post(card)s. Our born digital, multi-authored, multimedia theory of the en dehors garde comprises a wide range of perspectives, poses, and strategies.

In adopting a collaborative method and embracing new tools and forms, we aim to develop innovative forms of digital scholarship and theory commensurate to the en dehors garde. As Elisabeth Frost argues, to look back at history with the inclusion of female experimental writers and artists “challenges the way in which avant-gardism itself has been conceptualized.”5 Digital platforms offer new technologies for documenting and analyzing women’s negotiations with the historical avant-garde, allowing us to chart an alternative en dehors garde that proves to be neither a mere supplement to nor plea for inclusion within the current critical models of avant-garde formation. Open-source tools enable us to transform our scholarly methods and products in the same spirit of avant-garde innovation and collaboration that animated Mina Loy’s feminist designs a century ago.

Digital tools and platforms aren’t inherently liberating, feminist, or avant-garde, but they can be deployed in service of feminist designs. In conducting our own en dehors garde experiment, we wanted to see whether digital tools and platforms could help us transform the way we generate theory, produce knowledge, and distribute cultural power.

- The term en dehors garde was suggested by Nancy Selleck, Associate Professor of English, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, a feminist scholar of early modern literature and culture, as well as a dramaturg and theatre director at Harvard, Boston Directors’ Lab, and UMass Lowell. It seems appropriate that this idea was generated in conversation with a scholar who began her career outside academia as a professional ballet dancer. We are grateful to her for suggesting the term and elucidating its significance in ballet.

- Susan Rosenbaum, “The ‘do it yourself’ Avant-Garde: American Women Poets and Experiment,” A History of Twentieth-Century Women’s Poetry, p. 325, Edited by Linda A. Kinnhan, Cambridge University Press, 2016. 323-338.

- Sophie Seita,“The Politics of the Forum in Feminist Avant-Garde Magazines,” p.165, Journal of Moderni Literature, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Fall 2018), p.165.

- Hypothesis annotation, 5 April 2019.

- Elisabeth Frost,The Feminist Avant-Garde in American Poetry, p.xv, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2003.